Once tornado warnings were considered more dangerous than storms

Today, we expect tornadoes to come with a warning. Forecasts and alerts give people time to prepare for storms, often days in advance. For much of history, this was not the case. Survival depended less on information than on chance, and warnings came late, if at all.

Even when scientists such as John Park Finley identified atmospheric patterns that could be used to predict tornadoes in the 1880s, public officials in the United States refused to issue alerts containing the word “tornado.” The prevailing belief was that tornado predictions would cause panic, and that the panic would be more harmful than the storms themselves.

That reluctance persisted for decades. Even if officials had been willing to risk “causing panic,” there was no practical way to warn the public quickly. It was not until the early 1950s, with radios now a common household technology, that the United States began broadcasting severe weather alerts. In the following decades, alerting remained rooted in broadcast media.

As alerts became more frequent and more geographically targeted, systems like Specific Area Message Encoding (SAME) in the 1990s added digital headers to radio broadcasts: encoding metadata about the alert including time of issuance, origin of the alert, and even the specific weather event. The Emergency Alert System (EAS) soon extended that approach across radio and television.

Alerting had advanced significantly, but increasing alert volume and finer geographic targeting exposed the limits of broadcast-based alerting. Radio-based warnings could not be aggregated, analyzed, or distributed globally, and they lacked the precision, context, and interoperability required by modern systems.

Enter CAP

In November 2000, the US National Science and Technology Council issued a report titled "Effective Disaster Warnings". The report identified two core needs:

The need for a standard that would collect and instantly relay hazard warnings to people across a range of scales (locally, regionally, nationally), and

The need for automated systems that were also programmed to respond to hazards

A year later, over 130 emergency management, information technology, and telecommunications experts from around the world met to formalize the Common Alerting Protocol (CAP). While it wasn't a fast transition, today, almost every meteorological agency in the world issues severe weather alerts in CAP format, thanks in large part to an effort by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

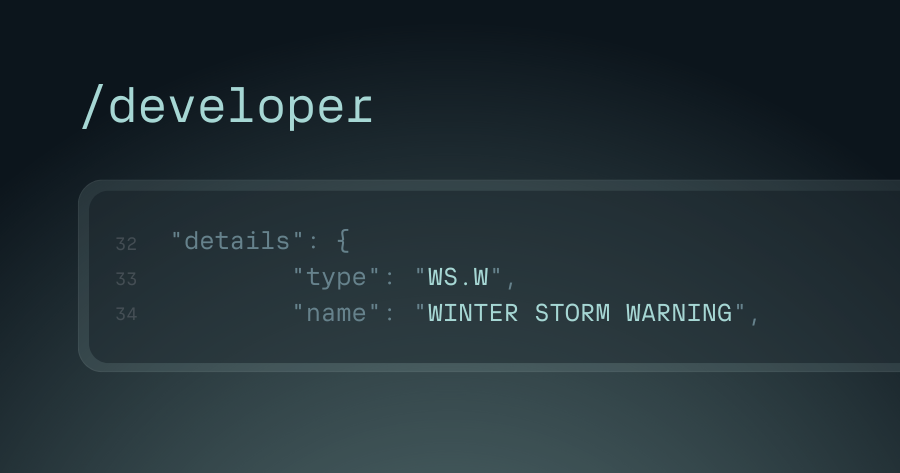

The CAP standard, an XML-based data format provides a lot of benefits over the one-off approaches meteorological agencies had before. The CAP specification:

Defined a consistent data structure (through extensible, CAP-specific XML profiles) for ingestion,

Defined a set of required elements for the most valuable information (such as urgency, severity, and certainty), and

Provided a universal method of updating and replacing previous alerts as new information was gathered or as models changed.

Turning CAP into a global alert system

CAP solved an essential problem by defining a common framework for alerts. But it takes a lot more than a framework to build a global alert system. The urgency of the underlying events, the number of issuing authorities across the globe, and the intrinsic variation in weather phenomenon and locally relevant names, all contribute significant hurdles to a truly global system.

Even with CAP, alerts are still:

Issued across many different providers and delivery systems: from modern REST APIs to legacy FTP servers and even XMPP (née Jabber) chat systems.

Frequently issued by multiple providers in a given country.

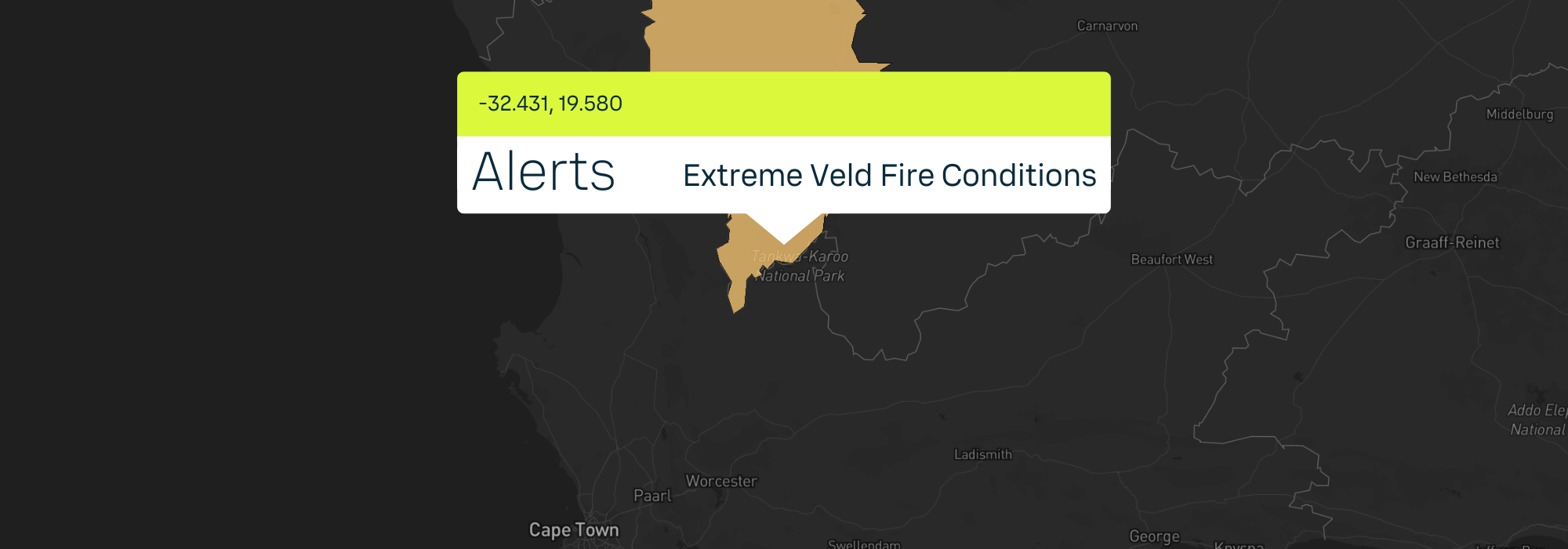

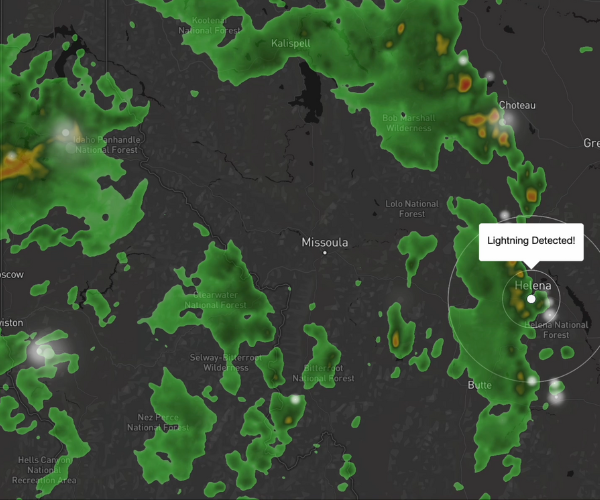

Labeled using inconsistent event naming and categorization, where the same underlying hazard may appear as distinct alert types such as “Veld Fire Conditions,” “Fire Danger,” “Extreme Fire Risk,” or “Red Flag Warning,” depending on the issuing agency.

Uneven in their adherence to the CAP specification, with missing required fields, nonstandard extensions, malformed XML, or inconsistent use of CAP values (e.g., urgency, severity, or certainty).

Often issued using ‘geocodes’, special identifiers which require finding and maintaining separate geographic data to enable lookup of actual impacted geometries.

Dependent on the quality of each agency’s infrastructure.

Often issued in only the local languages of each country.

Xweather has gone to significant lengths to solve the above difficulties. Xweather’s ingest system for alerts predated the availability of CAP-format alerts, which meant that as we worked to expand alerts coverage to additional countries, we were left maintaining very different systems. This came with all the usual caveats: multiple distinct codebases for the same product, different methods of fetching or listening for incoming alerts, and trying to fit different source data into the same schema for our end users. With all the above in mind, it was time to overhaul our alerts ingest system to take us through the next decade.

To solve these challenges, Xweather invested in core ingestion and normalization capabilities:

We maintain a robust list of different alert phenomena, negating the need for users to familiarize themselves with local terminology while still being able to quickly understand the risks.

We gracefully handle non-adherence to the CAP spec.

We ensure geometry is included in every alert available through our API and products.

We designed our systems to be robust, ensuring that data is always up to date.

We translated all non-English alerts into English (including Brazil, Mexico, and Japan) so that our users could easily read and understand severe weather events across the globe.

Yes, there are sheep alerts (and other very local hazards)

Consolidating alert types is a challenge; every issuing agency brings its own classification system, and some regions issue alerts that only make sense in their local context. When conditions are favorable for the development of bush or wildfires, South Africa issues alerts for "Veld Fire Conditions." Many other countries issue alerts for similar weather phenomena, but under different titles. To aid someone monitoring alerts across many territories, we categorize these alerts as a "Fire Weather" alert type, assigning an AW.FW code. Included in all alerts is basic styling information, such that it will appear the same on a map alongside similar fire weather alerts, whether they originating from within Europe, Brazil, the US, or South Africa.

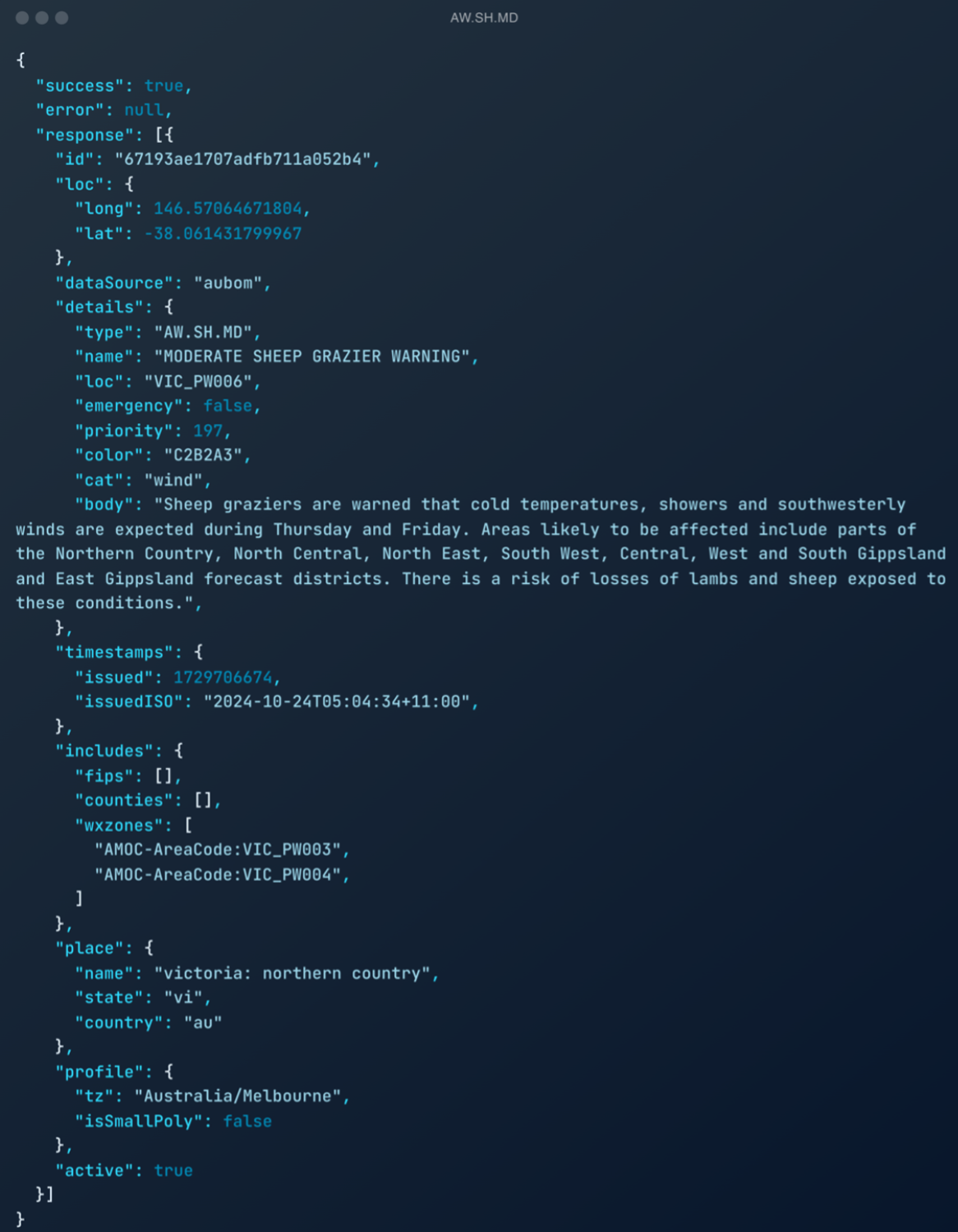

While we've come across a lot of interesting alert types, and one of our favorites comes out of Australia. When conditions turn cold and rainy, especially when combined with wind, this can be dangerous for livestock, sheep in particular. "Sheep Grazier Warnings" will be issued so sheep grazers can make adjustments to protect their livestock.

An example alert for a "Sheep Grazier Warning" issued by the Australia Bureau of Meteorology as retrieved from the Xweather API.

Sadly, my suggestion to expand our alert type codes to include emoji (AW.🐑.MD) was met with an assessment of "fun, but not a good idea."

Exceptions to every rule and why Japan doesn't use CAP

While most agencies have consolidated around CAP, Japan is an exception. Because Japan is home to some of the most tectonically active plate boundaries in the world, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) requires a system optimized for Earthquake Early Warnings (EEW), where latency is measured in milliseconds.

Just before CAP was being standardized, Japan overhauled their alerting system into multiple different subsystems, none of which use the CAP specification. This can be a real challenge for monitoring resources across multiple countries, as having to maintain separate importing systems for a single country is often a significant amount of technical overhead.

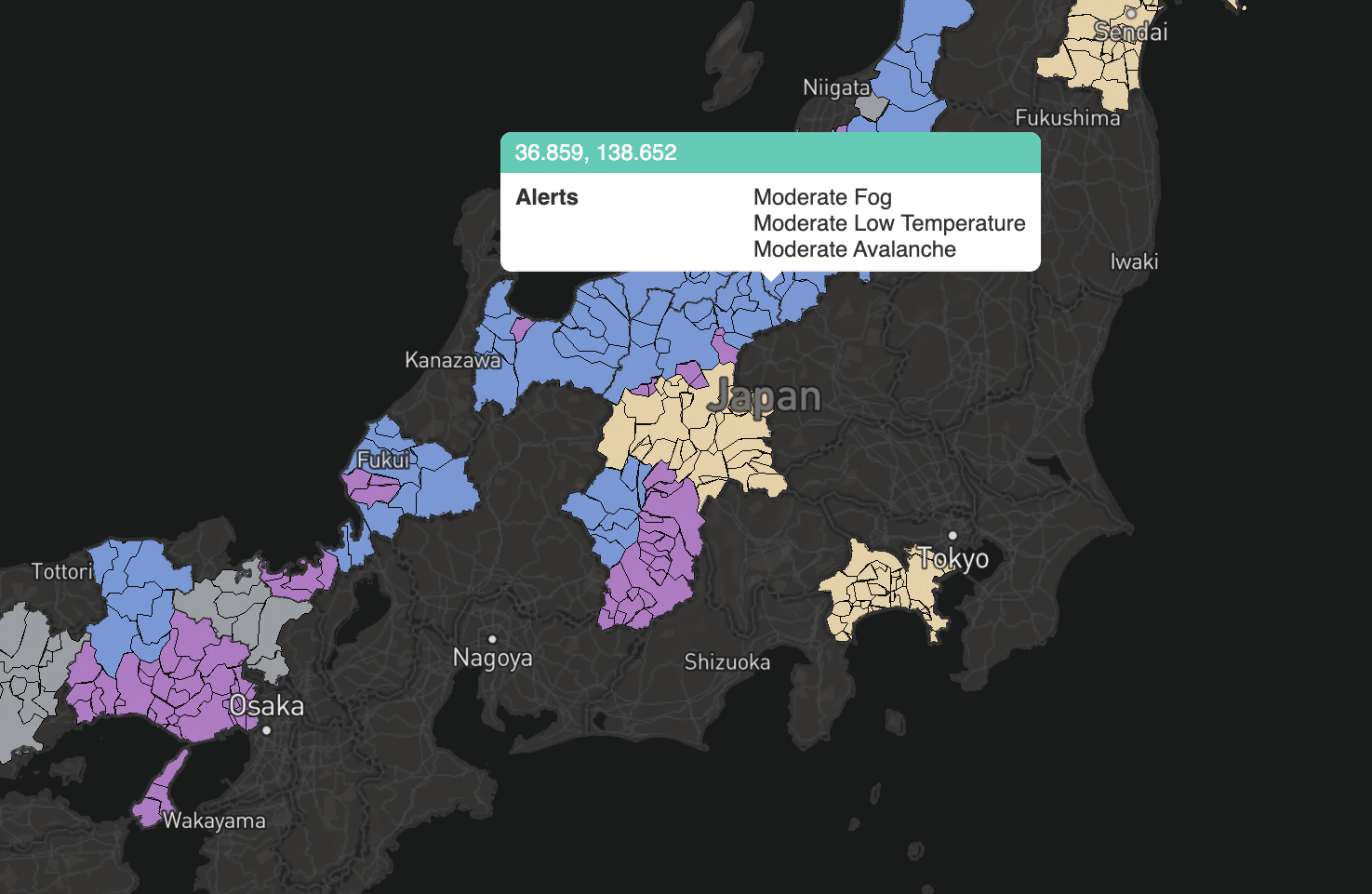

Xweather handles this at the ingestion level. Our custom Japan importer interfaces with these subsystems and maps the data to our global schema. We perform the normalization and translation, allowing you to query Japanese alerts through the same REST API and JSON format used for CAP-compliant territories.

Japanese Avalanche, Fog, and Temperature Alerts

Early warnings for all

Despite major advances in forecasting and alerting, access to timely warnings remains incomplete. In 2022, the United Nations launched the Early Warnings for All initiative, calling for universal access to early warning systems by 2027. The initiative highlights the reality that while alert standards and technologies exist, large parts of the world still lack the infrastructure, data integration, and delivery mechanisms needed to give people advanced warning of environmental hazards.

A breakthrough in global alerting

Xweather’s alerts API endpoints represent a fundamental step beyond consuming individual CAP feeds. They consolidate thousands of independently issued alerts across languages, formats, and infrastructures into a single, reliable global dataset.

Alerts have evolved from something that could barely be spoken into structured data that systems can integrate, analyze, and act on globally.